Chronic pain affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide and remains one of the most challenging problems in modern medicine. For decades, pain has largely been understood as a direct signal of tissue damage or disease. However, advances in pain science are reshaping this view. A growing body of research suggests that many forms of chronic pain are not driven by ongoing injury, but by changes in how the brain and nervous system process threat and sensation.

This concept, often referred to as neuroplastic pain, is transforming how researchers and clinicians think about pain, treatment, and recovery.

Pain as an Alert System, Not a Damage Meter

Pain is best understood as a protective alert system. Its primary function is to warn the body of potential danger and prompt protective behaviour. When you touch a hot surface or twist an ankle, pain encourages you to withdraw, rest, or seek care.

In acute injury, this system works remarkably well. However, problems arise when the alarm continues to fire long after tissues have healed.

In chronic pain, imaging and clinical studies increasingly show that pain can persist without ongoing tissue damage. Muscles, joints, nerves, and organs may appear structurally normal, yet pain remains intense and disabling. This disconnect has led scientists to explore how the brain itself contributes to the experience of pain.

Neuroplastic Pain: When the Brain Learns Pain

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to change, adapt, and map complex neural pathways based on experience. This capacity underpins learning, memory, and recovery after injury. However, it can also work in less helpful ways.

In neuroplastic pain, repeated pain signals, stress, fear, or threat perception can sensitise neural circuits involved in pain processing. Over time, the brain becomes more efficient at producing pain, even in the absence of physical harm. In effect, pain becomes a learned response.

Research using functional MRI has shown altered activity in brain regions associated with emotion, threat detection, and attention in people with chronic pain. These findings support the idea that chronic pain is not “imagined” or psychological in a dismissive sense, but rather a real, biologically generated experience driven by the central nervous system.

Importantly, this does not mean the pain is voluntary or under conscious control. The brain generates pain automatically, based on its assessment of danger.

Pain Science Challenges Traditional Models

Traditional biomedical models have focused heavily on identifying structural causes of pain and treating them with medication, injections, or surgery. While these approaches are essential for many conditions, they often fall short in chronic pain syndromes such as:

- Chronic low back pain

- Fibromyalgia

- Chronic migraine

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Complex regional pain syndrome

Pain science has revealed that in many of these conditions, the nervous system itself becomes hypervigilant. The brain interprets normal sensations, movements, or internal signals as threatening, triggering pain as a protective response.

This shift in understanding has opened the door to new therapeutic approaches that aim not to suppress pain signals, but to retrain the brain and calm the nervous system.

Pain Reprocessing Therapy: A New Therapeutic Approach

One emerging approach is pain reprocessing therapy (PRT). This method is grounded in the idea that if pain is generated by learned neural pathways, those pathways can be modified or unlearned.

Pain reprocessing therapy focuses on helping individuals reinterpret pain sensations as non-threatening, reduce fear associated with pain, and gradually recondition the nervous system. Techniques may include:

- Education about pain neurobiology

- Cognitive reframing of pain sensations

- Exposure to feared movements or activities

- Emotional awareness and regulation

Clinical trials have shown promising results, particularly in chronic back pain, where some participants report significant reductions or even resolution of pain after treatment.

For the life science and healthcare community, PRT represents a shift away from symptom suppression and toward addressing the neural mechanisms underlying chronic pain.

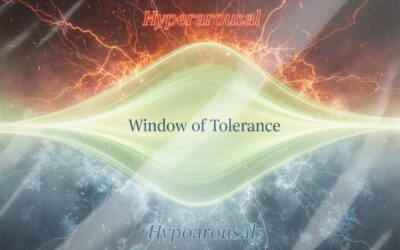

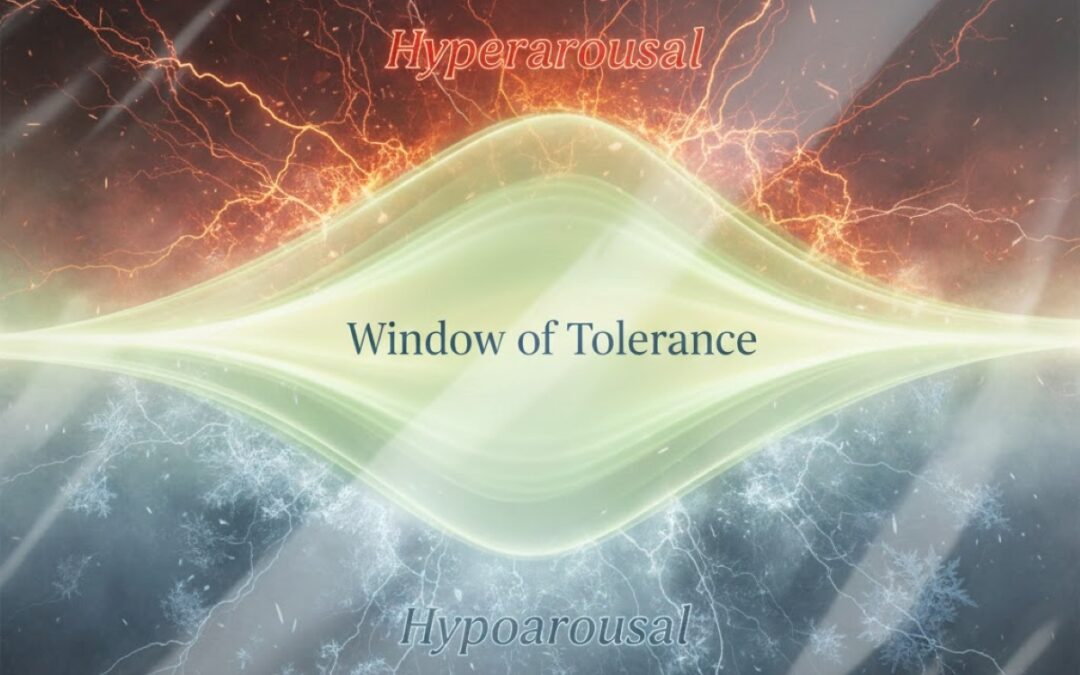

Calming the Nervous System

Central to the management of neuroplastic pain is regulation of the nervous system. Chronic pain is often associated with a persistent state of physiological threat, characterised by heightened sympathetic nervous system activity.

Interventions that promote nervous system calming can reduce pain sensitivity and improve outcomes. Among the most studied techniques is controlled breathing.

Slow, diaphragmatic breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system, which counteracts stress responses and reduces neural excitability. Regular breathing practices have been shown to:

- Lower pain intensity

- Reduce anxiety and hypervigilance

- Improve autonomic balance

- Enhance emotional regulation

Other approaches that support nervous system regulation include mindfulness and graded movement patterns. These interventions do not suggest that pain is “all in the mind”, but rather recognise that the brain and body operate as an integrated system.

Implications for Research and Clinical Practice

The recognition of neuroplastic pain has significant implications for how chronic pain is studied and treated.

For researchers, it underscores the importance of investigating central nervous system mechanisms alongside peripheral pathology. For clinicians, it highlights the need for multidisciplinary approaches that combine education, behavioural therapy, physical rehabilitation, and nervous system regulation.

It also raises important questions about the long-term reliance on pharmacological treatments, particularly opioids, which address symptoms without altering the underlying neural drivers of pain.

A Changing Narrative Around Chronic Pain

Perhaps the most important shift brought by pain science is a change in narrative. Patients with chronic pain are increasingly being told not that their pain is imaginary, but that it is real, reversible, and rooted in the brain’s protective wiring.

This perspective can be empowering. Understanding pain as an overactive alarm system rather than a sign of damage opens new pathways to recovery and reduces fear, stigma, and hopelessness.

Looking Ahead

Neuroplastic pain research is still evolving, but its impact is already reshaping pain management. As evidence grows, therapies that target brain-based pain mechanisms are likely to become more integrated into mainstream care.

For the life science community, chronic pain represents both a major unmet medical need and an opportunity to rethink how biological systems generate and sustain suffering. By combining neuroscience, psychology, physiology, and patient-centred care, the field is moving closer to treatments that address pain at its source.

Chronic pain may not always signal damage. In many cases, it signals a nervous system that has learned to protect too well. Understanding that distinction could change the future of pain care.