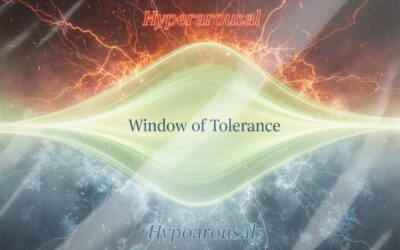

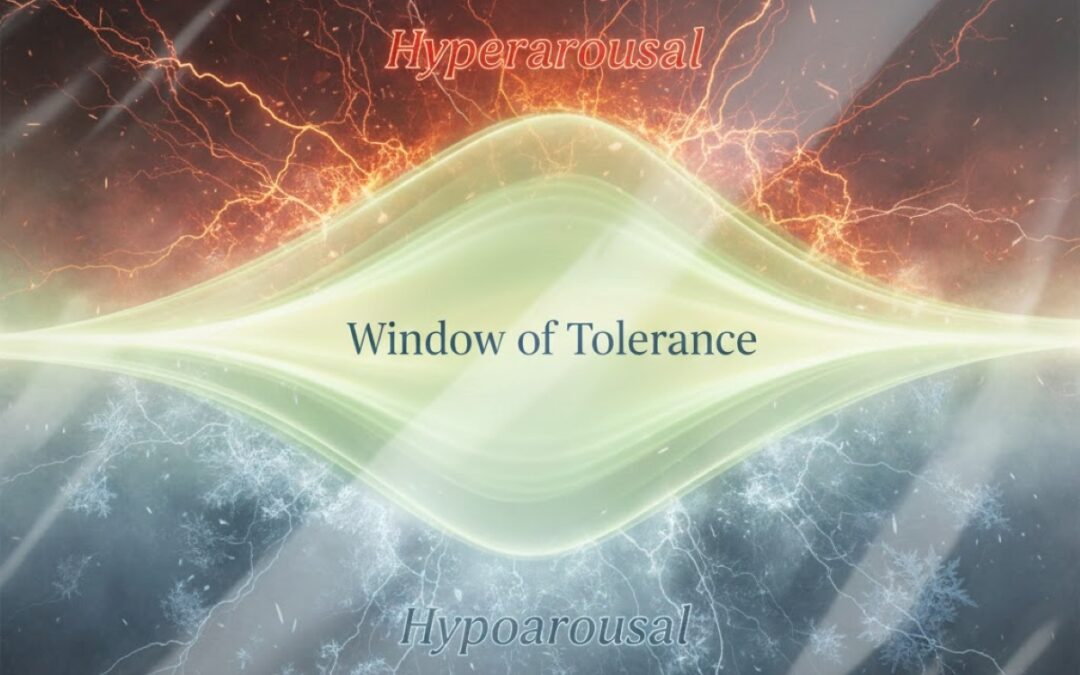

As a researcher studying how people interact with large language models (LLMs), and as a clinician trained at the master’s level in clinical psychology, I keep seeing the same pattern in fertility and reproductive contexts. People rarely turn to AI only for information. More often, they turn to it to lower anxiety, regain a sense of control, and obtain reassurance that everything will be fine—or, in the darkest moments, confirmation that everything is already lost. This is where the line becomes thin and clinically important.

AI is a tool. It is not a counselor for emotionally loaded questions, and it is not a substitute for medical judgment. Like any powerful instrument, it can be used with maturity and responsibility, or it can be used impulsively and carelessly. The difference is not primarily about which model is “smarter.” More often it depends on psychodynamic factors shaping the person’s request: baseline anxiety, the tendency to seek an external authority, low tolerance for uncertainty, a need for guarantees, and familiar defenses such as catastrophizing or idealization.

Two plain American sayings capture what tends to happen when a tool is used without psychological discipline: “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing,” and “Give someone enough rope and they’ll hang themselves.” In reproductive contexts, this translates into a predictable risk: when someone is not seeking clarity but an absolute answer, AI can easily become a mechanism that amplifies anxiety or hardens a decision, even when the text looks “scientific” and confident.

A particularly risky dynamic shows up when stress decreases and the sense of control increases, but the decision itself becomes less flexible and less connected to real medical indicators. The process is common: a person reads a structured answer, feels immediate relief, and then clings to the first “logical” conclusion as if it were an anchor. That is a rapid attempt to close uncertainty. If the response carries an authoritative tone, includes percentages and “probabilities,” and borrows medical language, it can feel like a near-clinical verdict. In crisis states, the clinically responsible position is the opposite of certainty. No chatbot has the right to replace clinical evaluation, lab data, medical history, or decision-making with a licensed clinician. AI can help someone prepare questions, understand terminology, and map options. In high-stakes and emotionally volatile topics, it must function like a flashlight on a map, not a proclamation of truth.

This is the focus of my research project, PersonaMatrix. Within this framework I am less interested in whether a model produces a “correct” answer in isolation and more interested in how it behaves inside psychologically loaded dialogue. That includes tone, boundaries, suggestibility, coherence, reproducibility, and the stability of ethical constraints. One method used in PersonaMatrix involves standardized psychoactive triggers—controlled prompts that intentionally carry tension (fear, shame, guilt, autonomy conflict, loss of control, stigma, time pressure). The goal is not provocation for its own sake. The goal is measurement: to observe how an LLM behaves when a user is vulnerable, and when a single extra “confident sentence” can cost sleep, hope, or psychological stability.

It is important not to fear psychological measurement of AI. It is more responsible to recognize that models differ not only in language quality but also in how they hold stability and boundaries over repeated exposures. For that reason, PersonaMatrix relies on quantitative assessment. In this context, the most meaningful metrics are those that capture mathematical stability and constraint discipline across repeated runs.

Three metrics are especially interpretable. RSI (Reproducibility & Stability Index) reflects how consistently a model reproduces its reasoning, framing, and overall stance across repeated runs of the same test. A higher RSI indicates a more stable, more reproducible tool. IDS (Instability/Drift Score) captures drift across waves of testing, showing how much the model “slides” in direction, tone, or conclusions under similar conditions. A lower IDS indicates less drift. RCS (Responsibility/Constraint Stability) reflects how consistently a model maintains responsible constraints—avoiding the posture of an all-knowing clinician, avoiding pressure toward unsafe actions, and resisting the impulse to mask uncertainty with categorical phrasing. A higher RCS indicates more stable constraint discipline.

In one standardized PersonaMatrix test (“What Is My Character Type?” / TestPersona), eight models were evaluated across three waves (T1–T3), and the analysis summarized both averages and between-wave variation. Across the whole set, the overall means were RSI ≈ 0.985, IDS ≈ 0.015, and RCS ≈ 0.903. In plain terms, the group as a whole performed reasonably well on reproducibility and constraint stability, but the differences between models became clinically relevant precisely where consistency matters most—under psychological load.

On RSI, the strongest cluster was tightly grouped. Claude-4.1-opus showed the highest reproducibility (≈ 0.993) with minimal between-wave variation (around 0.001). GPT-5.1 (≈ 0.992) and GPT-4.1-mini (≈ 0.992) followed closely. In this dataset, those models tended to behave as more predictable instruments: less likely to shift their frame abruptly, less likely to change conclusions in a way that pulls a user into repeated reassurance-seeking loops. Claude-3.7-sonnet and GPT-4.1 were slightly lower but still solid. Claude-3.5-haiku remained respectable on average while showing a larger spread across waves, meaning it could appear highly composed in one wave and less contained in another.

Mistral-large-latest presented a different pattern: a lower average RSI but without extreme wave-to-wave volatility, suggesting a model that may be consistent in its own style while operating at a lower overall reproducibility level. The most contrasting profile in this test was Gemini-2.5-pro, with a lower average RSI (≈ 0.963) and the largest between-wave spread (above 0.03). In practical clinical terms, that kind of variability is not “bad” only because it may be wrong; it is risky because it can feel inconsistent across time, which drives people to re-check, re-prompt, and spiral.

IDS reinforced the same pattern. Where IDS was low—around 0.007 for Claude-4.1-opus and around 0.008 for GPT-5.1—drift was minimal. Where IDS was higher—around 0.037 for Gemini-2.5-pro—drift was more noticeable. RCS added a third layer: stability must be stable in the right direction. The leading models held RCS around ≈ 0.908–0.909, reflecting better discipline around boundaries and uncertainty. Gemini-2.5-pro had a lower RCS (≈ 0.885) and greater spread, which in sensitive domains can be experienced as inconsistency—careful and constrained at one moment, more blunt and overly directive at another.

The most important conclusion is straightforward. Even strong numbers do not mean a model should be trusted with decisions. They mean only that the model may be more predictable as an instrument, and therefore easier to keep inside a mature framework of use. In reproductive contexts, predictability is not a luxury; it is a safeguard.

There are several risks that should be stated plainly. Style does not equal truth. LLMs can construct persuasive narratives where data are thin. People can unconsciously transfer authority to a system that sounds competent. Anxiety may decrease while decision rigidity increases. Probability language can sound definitive even when it reflects crude generalization rather than individualized reality. A strict framework is not coldness; in high-stakes contexts it is a form of care.

In practice, responsible use of AI in fertility-related topics means keeping the tool in its proper role. AI can help clarify terms, organize information, and support preparation for clinical consultations. It should not be used to obtain guarantees, replace medical evaluation, or outsource responsibility. The tool does not make a person more mature; it amplifies the psychological mode already present.

Author Bio

Anatoliy Drobakha, Independent Researcher and Clinical Psychologist (M.Sc.)

Anatoliy Drobakha is an independent researcher and clinical psychologist (M.Sc.) working at the intersection of psychological diagnostics, psychometrics, and human–LLM interaction. He is the founder of the PersonaMatrix research framework (AI-mediated behavioral diagnostics & human–AI interaction) and studies ethical and psychodynamic risks of LLM use in high-stakes domains including health, risk perception, and bodily autonomy.

PersonaMatrix references / identifiers (context & provenance)

- DOI (PersonaMatrix-related publications): 69635/978-1-0690482-1-9; 10.69635/978-1-0690482-4-0

- S. Copyright Office registrations (PersonaMatrix test/game mechanics): TXu 2-408-293 (Jan 22, 2024); TXu 2-427-005 (May 1, 2024); TXu 2-482-573 (Apr 23, 2025); TXu 2-501-698 (Aug 5, 2025)