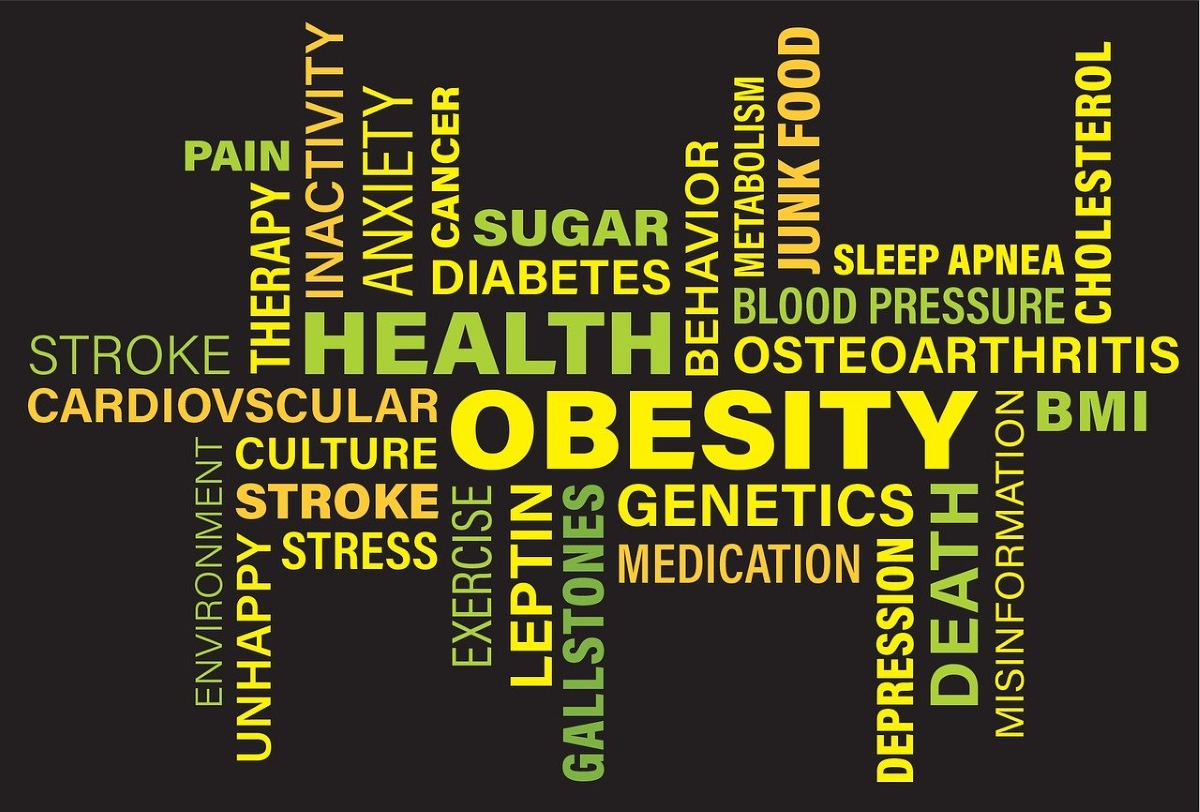

For decades, obesity has been defined and diagnosed primarily using body mass index (BMI), a simple ratio of weight to height. While BMI has been widely adopted for its convenience and scalability, a growing body of research now suggests that it may be an incomplete and sometimes misleading measure of metabolic health and disease risk. A new wave of obesity redefinition studies is challenging the dominance of BMI and reshaping how obesity may be classified, studied, and treated in the future.

These studies are gaining attention across academia, healthcare systems, and the life sciences industry, with implications for clinical trial design, drug development, diagnostics, and regulatory frameworks.

Why BMI Is Under Scrutiny

BMI was originally developed in the 19th century as a population-level statistical tool, not a clinical diagnostic. Despite this, it has become embedded in medical guidelines, insurance policies, and public health strategies worldwide. However, researchers have long pointed out its limitations.

BMI does not distinguish between fat and lean mass, nor does it account for fat distribution, metabolic health, ethnicity, age, or sex differences. As a result, individuals with the same BMI can have vastly different health profiles. Some people classified as obese by BMI may have relatively normal metabolic markers, while others with a “normal” BMI may carry high levels of visceral fat and significant cardiometabolic risk.

Large-scale epidemiological studies have reinforced these concerns, showing weak or inconsistent correlations between BMI alone and outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes progression, and mortality when metabolic markers are taken into account.

Shifting Toward Metabolic Health-Based Definitions

Recent obesity redefinition studies are increasingly focused on metabolic dysfunction rather than body size alone. Researchers are proposing frameworks that incorporate insulin resistance, lipid abnormalities, inflammation, liver fat accumulation, and ectopic fat deposition as central features of obesity-related disease.

One emerging concept is the distinction between “adiposity-based chronic disease” and body weight. This approach reframes obesity as a condition defined by dysfunctional adipose tissue and impaired metabolic regulation, rather than excess weight per se. Under this model, obesity becomes a chronic, relapsing disease with biological drivers, aligning it more closely with conditions such as type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

This shift has important implications for patient stratification, allowing clinicians and researchers to identify individuals at highest risk and intervene earlier, even when BMI appears normal.

Imaging and Biomarkers Enter the Definition Debate

Advances in imaging technologies are playing a growing role in obesity redefinition research. MRI, CT scans, and ultrasound-based tools can now quantify visceral fat, liver fat, and muscle quality with increasing precision. Studies consistently show that visceral and ectopic fat are far more predictive of metabolic and cardiovascular risk than total body fat or BMI.

In parallel, blood-based biomarkers are being evaluated as tools to redefine obesity. Markers of insulin resistance, inflammatory cytokines, adipokines, liver enzymes, and lipid particle profiles are increasingly used to identify metabolically unhealthy states independent of body size.

For the life sciences industry, this biomarker-driven approach opens new opportunities for diagnostics, companion tests, and more targeted therapeutic development.

Implications for Drug Development and Clinical Trials

The redefinition of obesity has significant consequences for how clinical trials are designed and interpreted. Historically, many obesity trials have relied on weight loss as the primary endpoint. While weight reduction remains clinically meaningful, redefinition studies suggest that improvements in metabolic health may be a more relevant measure of long-term benefit.

This perspective aligns closely with the development of newer anti-obesity and metabolic drugs, including GLP-1 receptor agonists, dual and triple incretin therapies, and emerging agents targeting adipose tissue biology, inflammation, or energy expenditure. These therapies often deliver benefits beyond weight loss, such as improved glycaemic control, reduced cardiovascular risk, and better liver health.

Redefining obesity could support broader indications, new endpoints, and more nuanced regulatory discussions around what constitutes clinical success.

Regulatory and Health System Considerations

Health authorities and professional societies are beginning to acknowledge the limitations of BMI, though widespread guideline changes remain gradual. Some organisations have called for BMI to be used as a screening tool rather than a diagnostic endpoint, supplemented by metabolic and clinical assessments.

Redefinition studies also raise questions for reimbursement and access to treatment. Many healthcare systems and insurers currently rely on BMI thresholds to determine eligibility for obesity therapies. A move toward metabolic criteria could expand access for some patients while excluding others who meet BMI thresholds but lack metabolic risk.

For policymakers, the challenge will be balancing simplicity, equity, and scientific accuracy in population-level recommendations.

Equity, Ethnicity, and Global Relevance

Another driver behind obesity redefinition research is the recognition that BMI performs differently across populations. Studies show that people of Asian, African, and Middle Eastern ancestry may develop metabolic complications at lower BMI thresholds than populations of European descent.

Incorporating ethnicity-specific risk markers, body composition measures, or metabolic thresholds could improve global relevance and reduce disparities in diagnosis and treatment. However, this also adds complexity to screening programmes and clinical decision-making.

The Future of Obesity Classification

Obesity redefinition studies are not seeking to eliminate BMI entirely, but to place it within a broader, more biologically grounded framework. The emerging consensus is that obesity is best understood as a heterogeneous condition with multiple subtypes, drivers, and clinical trajectories.

For the life sciences sector, this shift represents both a challenge and an opportunity. Companies developing therapeutics, diagnostics, digital health tools, and preventive strategies will need to adapt to more nuanced definitions of disease. At the same time, more precise classification could enable better targeting, improved outcomes, and stronger evidence of value.

As research continues, obesity may increasingly be defined not by a number on a scale, but by measurable disruptions in metabolic health. If adopted widely, this redefinition could transform how obesity is studied, regulated, and treated across healthcare systems worldwide.