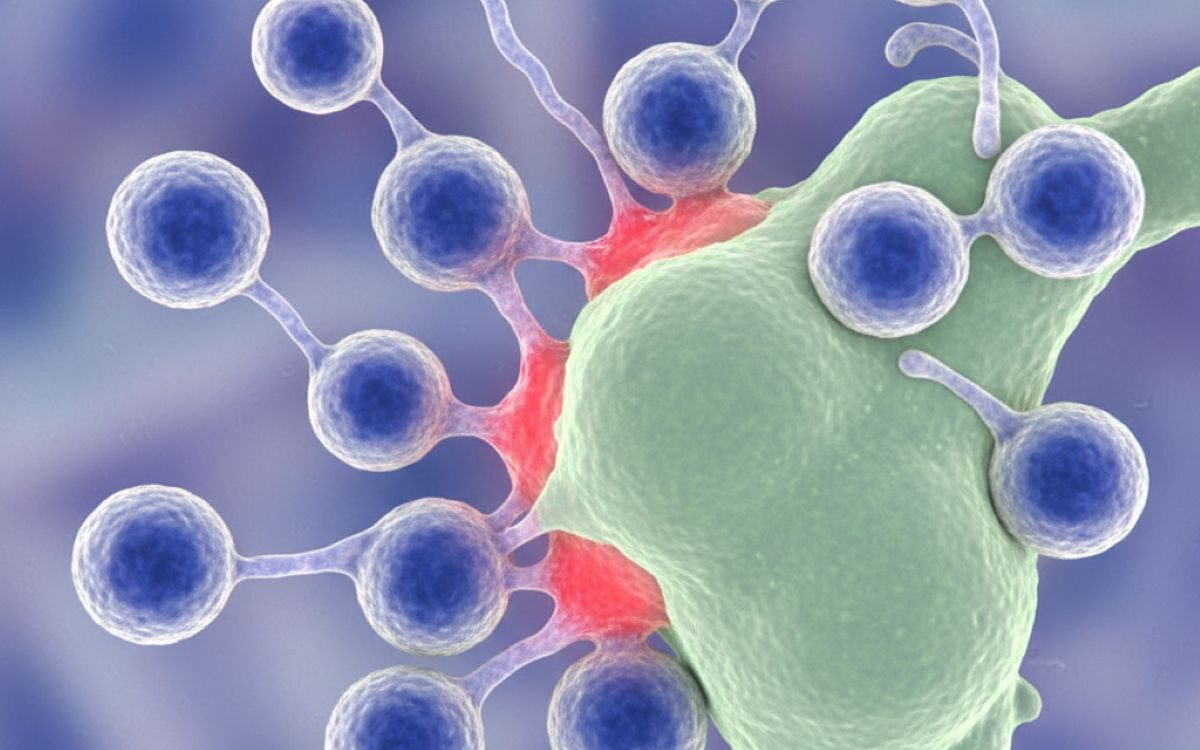

As the population ages, one of the major challenges facing public health is that vaccines tend to become less effective in older adults. A growing body of research increasingly points to specific changes in T cells, critical components of the immune system, as a key underlying reason. These changes, often grouped under the term immunosenescence, help explain why older individuals are more vulnerable to infection and why they often generate weaker immune responses to vaccination.

Why vaccine responses decline with age

Vaccination relies on the immune system’s ability to recognise an antigen, generate a memory response through B cells and T cells, and then mount an effective defence when the pathogen or a related agent is encountered again. However, research shows that as people age, the T cell compartment undergoes both quantitative and qualitative changes that undermine this process.

One key change is the decline in the number and diversity of naïve T cells, those that have not yet encountered antigens. Studies show that in adults over 55, counts of naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells decline markedly with age, while more differentiated, memory and effector type T cells accumulate. Without sufficient naïve T cells, the ability to respond to new vaccine antigens or novel pathogens is reduced.

Another major issue is that the thymus, where T cells mature, undergoes involution or shrinkage with age, limiting new T cell generation. Moreover, older T cells often show changes in metabolism, signalling and regulatory function that reduce their proliferative capacity and adaptability.

How these T cell changes translate into weaker vaccine responses

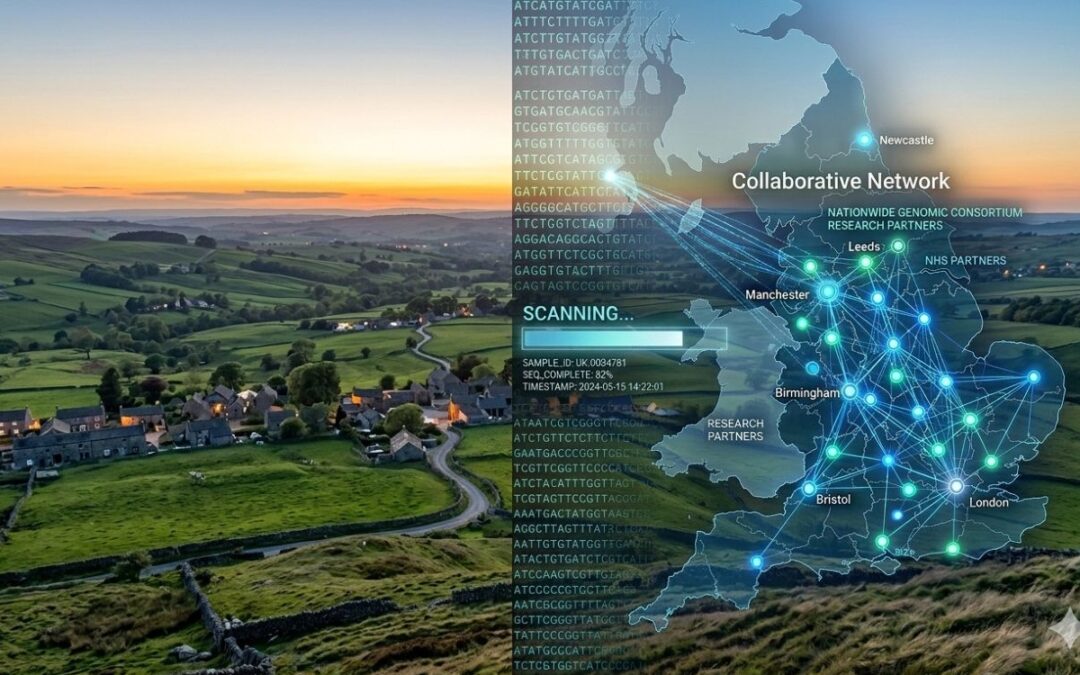

Recent immune profiling studies provide deeper insight into the mechanism. One study involving over sixteen million immune cells from adults aged 22 to 65 showed that memory T cells in older individuals shift toward a T helper 2 like phenotype, which is less effective at helping B cells produce high quality antibodies after vaccination.

Additionally, research found that older adults with lower percentages of specific naïve T cell subsets, such as CD31+ naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, had significantly poorer responses to multiple vaccines including influenza, pneumococcal and COVID 19 vaccines.

Furthermore, the germinal centre reaction, the process by which B cells refine antibodies, also declines with age partly because of altered T cell help from T follicular helper cells. This diminishes antibody quality and durability after vaccination.

Broader immune dysfunction: Inflammaging, regulatory imbalance and memory skewing

Age related changes also manifest through a background of chronic low grade inflammation, often called inflammaging, which affects immune cell signalling and responsiveness.

In older adults, T cells often become more terminally differentiated or senescent, expressing markers such as KLRG1 or CD57, having reduced proliferative capacity and sometimes secreting inflammatory cytokines inappropriately. Such changes can interfere with the ability of the immune system to mount coordinated responses after vaccination.

Implications for vaccine strategy and older populations

Understanding how T cells change with age has significant implications. If older adults mount weaker responses to standard vaccines, it becomes critical to adapt vaccination strategies accordingly. Reviews in The Lancet Infectious Diseases and other journals argue that vaccines for older people may need enhanced adjuvants, higher antigen doses, or novel designs to compensate for the aged immune system.

For example, influenza and pneumococcal vaccines recommended for older adults often include stronger adjuvants or higher antigen contents. Still, researchers argue that even more tailored approaches may be required, such as vaccines designed specifically to engage the older immune system’s altered T cell environment.

Moreover, T cell phenotyping, for example measuring naïve T cell counts, may ultimately help predict who will respond poorly to vaccination and guide personalised booster strategies.

Challenges and research gaps

While the evidence is strong, several research gaps remain. Many studies focus on peripheral blood samples rather than lymphoid tissues where much of the immune activation occurs. Longitudinal data on how T cell changes correlate directly with clinical vaccine failure are still limited. Also, the interplay between infection history, such as chronic cytomegalovirus infection, lifestyle factors and T cell ageing requires further elucidation.

Outlook: Strengthening vaccine responses in later life

As populations age globally, strengthening vaccine performance in older adults is a public health imperative. Strategies that look beyond simply giving booster shots, towards addressing T cell ageing, improving immune resilience and tailoring vaccines, are gaining ground. Optimising vaccine design for ageing immune systems, integrating immune profiling to identify low responders, and possibly developing therapeutics that rejuvenate key T cell compartments are among the future directions.

In sum, the weakness of vaccine responses in older people is not simply a matter of age but a reflection of profound changes in T cell biology. Recognising and addressing these changes offers a path to better protection for one of the most vulnerable segments of the population.