Antibiotics are one of the greatest success stories in modern medicine. They transformed once-deadly infections into treatable illnesses, made routine surgery possible, and helped extend human life expectancy worldwide. From treating pneumonia to protecting patients during cancer therapy and organ transplants, antibiotics sit quietly behind much of today’s healthcare. But that foundation is beginning to crack. Antibiotic resistance, also known as antimicrobial resistance or AMR, is spreading globally and weakening the medicines that modern medicine depends on.

Unlike outbreaks that arrive suddenly and demand immediate attention, antibiotic resistance develops slowly. It has been built over years in hospitals, communities, farms, and the environment. Because it does not appear as a single dramatic event, it often goes unnoticed outside scientific and medical circles. This slow and steady spread is why experts increasingly refer to antibiotic resistance as a silent pandemic. It is global, persistent, and dangerous, even if it rarely dominates the news.

The scale of the problem is now clear. A major global study published in The Lancet found that in 2019, an estimated 1.27 million deaths worldwide were directly caused by drug-resistant bacterial infections, while nearly 5 million additional deaths were associated with infections in which resistance played a role (Murray et al., 2022). These figures place antibiotic resistance among the leading causes of death globally, alongside well-known infectious diseases such as HIV and malaria.

More recent modeling suggests the situation could worsen. Projections extending to 2050 indicate that without strong and sustained intervention, millions more people could die each year from drug-resistant infections, particularly in regions with limited access to diagnostics and effective treatments (Murray et al., 2024). These estimates make clear that AMR is not a distant future threat, but a growing crisis already shaping global health outcomes.

To understand why resistance is so difficult to stop, it helps to understand how bacteria adapt. Bacteria multiply quickly and change easily. When antibiotics are used, they kill bacteria that are sensitive to the drug, but those with traits that allow survival may remain. These surviving bacteria then reproduce, passing on their resistance. Scientists recognized this process early in the antibiotic era, with resistance to penicillin documented just a few years after its widespread introduction.

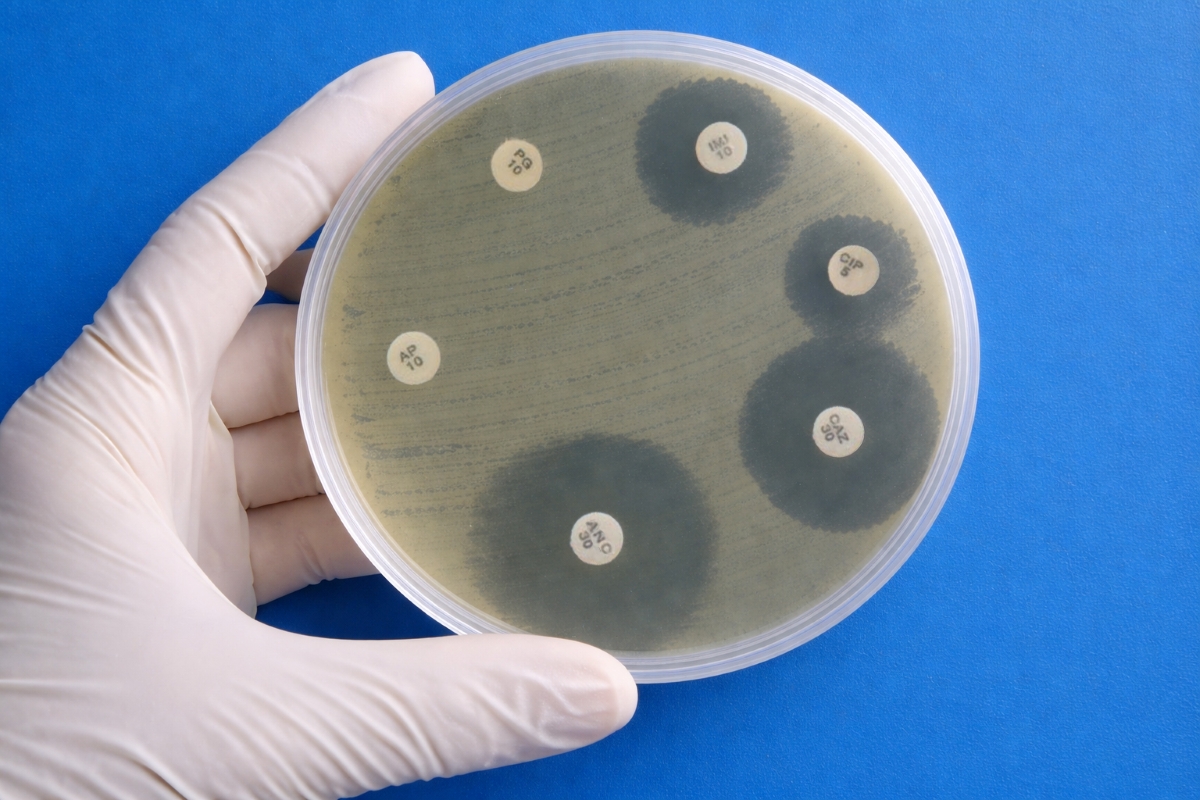

Bacteria can develop resistance in several ways. Some acquire random genetic changes that alter the antibiotic’s target so the drug can no longer work effectively. Others gain resistance genes from nearby bacteria through gene-sharing processes such as direct contact, uptake of genetic material from the environment, or transfer via viruses that infect bacteria. These resistance genes may allow bacteria to break down antibiotics, block the drug from entering the cell, or pump it back out once inside. Some bacteria are naturally resistant to certain antibiotics, while others acquire resistance over time as antibiotics are used more widely. Together, these mechanisms allow bacteria to adapt rapidly and collectively, making resistance difficult to reverse (Davies & Davies, 2010; Blair et al., 2015; Munita & Arias, 2016).

What has changed in recent decades is not the existence of resistance, but how quickly it spreads. Antibiotics are now used extensively across human medicine, veterinary care, agriculture, and aquaculture. In healthcare settings, antibiotics are sometimes prescribed when they are not needed, such as for viral infections. In agriculture, antibiotics are often given to healthy animals to prevent disease or promote growth. These practices expose large numbers of bacteria to low levels of antibiotics over long periods, creating ideal conditions for resistance to develop and spread across people, animals, and the environment (Holmes et al., 2016).

Global surveillance efforts confirm these trends. The World Health Organization’s Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System reports rising resistance to commonly used antibiotics in many parts of the world. In some regions, more than half of tested bacterial infections no longer respond reliably to first-line treatments (World Health Organization, 2023).

For patients and healthcare providers, the consequences are increasingly visible. Resistant infections often require longer hospital stays, more complex treatments, and medications that can have serious side effects. A large European study estimated that antibiotic-resistant infections cause tens of thousands of deaths each year in Europe alone, along with substantial healthcare costs (Cassini et al., 2019). Similar patterns are being reported globally.

The effects of antibiotic resistance extend far beyond individual infections. Antibiotics protect patients during surgery, childbirth, cancer treatment, and intensive care. Without reliable antibiotics, many routine medical procedures become riskier. As resistance grows, the safety net that antibiotics once provided begins to unravel, threatening the stability of modern healthcare.

Despite long-standing warnings, the development of new antibiotics has slowed dramatically. Very few truly new antibiotics have reached the market in recent decades. One major reason is economics. Antibiotics are taken for short periods and are deliberately used sparingly to slow resistance, which makes them less profitable than drugs taken daily for chronic conditions. As a result, many pharmaceutical companies have reduced or abandoned antibiotic research altogether (Theuretzbacher et al., 2023).

Recognizing that traditional market forces have failed to sustain antibiotic innovation, policymakers have begun exploring new incentive models. In the United States, the proposed PASTEUR Act, short for Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance, aims to encourage antibiotic development while promoting responsible use. The legislation would create a subscription-style payment system in which the federal government pays pharmaceutical companies a fixed annual fee for access to critically important antibiotics, regardless of how much of the drug is sold. By separating profits from sales volume, supporters argue that the model could bring companies back into antibiotic research without encouraging overuse of new drugs. While the PASTEUR Act has not yet been enacted, it reflects a growing recognition that policy innovation is essential to addressing antibiotic resistance (Outterson et al., 2021; Rex et al., 2023).

Researchers are also exploring new scientific approaches to address the problem. These include treatments that use viruses to target bacteria, drugs that weaken bacteria rather than kill them directly, and faster diagnostic tools that help doctors choose the right treatment sooner. Improving how existing antibiotics are used remains equally important. Antibiotic stewardship programs have been shown to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use without harming patient outcomes (Kumar et al., 2025).

Experts increasingly emphasize a One Health approach, which recognizes that human health is closely linked to animal and environmental health. Because resistant bacteria move between people, animals, food, and water, effective solutions must address all these areas together (World Health Organization, 2022).

The economic risks are also substantial. The World Bank has warned that unchecked antibiotic resistance could slow global economic growth and worsen poverty, particularly in countries with fewer healthcare resources (World Bank, 2017).

Antibiotic resistance does not announce itself with lockdowns or daily case counts, but its effects are already being felt. It is a slow-moving global crisis that threatens to make common infections dangerous again and modern medical care less certain. Scientists have warned about this problem for decades. Whether antibiotic resistance remains a silent pandemic or becomes a global priority will depend on how quickly the world chooses to act.

The themes in this article strongly reflect the work underway in my own college at Rochester Institute of Technology, where our faculty and students explore the biology of antibiotic resistance and pursue new antimicrobial strategies. As dean and an active scientist, I work alongside colleagues who share a mission that extends beyond simply educating, mentoring, and training students, we also aim to inspire them. Our goal is to ensure that students are not only knowledgeable but also motivated and prepared to confront today’s and tomorrow’s scientific challenges, including antimicrobial resistance. Meeting these challenges will require a truly holistic approach, because science cannot succeed with only researchers at the lab bench; it also depends on policymakers, communicators, ethicists, and many other essential contributors. For the future scientists we train at RIT, antibiotic resistance will not merely be a subject of study, but a real-world problem they are equipped to help solve through interdisciplinary collaboration.

Biography

Dr. André O. Hudson

Dr. André O. Hudson is a biochemist and Dean of the College of Science at the Rochester Institute of Technology, where he also serves as Professor in the Thomas H. Gosnell School of Life Sciences. He earned his B.S. in Biology from Virginia Union University and his Ph.D. in Plant Biology and Pathology from Rutgers University. Dr. Hudson’s research spans biochemistry, genomics, structural biology, and microbiology, with one of the major pillars of his work focused on antibiotic resistance and the discovery and characterization of novel antimicrobial compounds. He has published widely in peer-reviewed journals, secured competitive research funding, and mentors the next generation of scientists committed to solving pressing biomedical challenges.

Media Contact: Cynthia Lieberman, LieberComm