Emerging Evidence of Alternative Motility

For decades, scientists have believed that bacterial movement relied almost entirely on the rotation of whip-like flagella, which propel cells through liquids or across surfaces. However, new research has revealed that some bacteria can move without these structures, using unexpected physical and biochemical strategies.

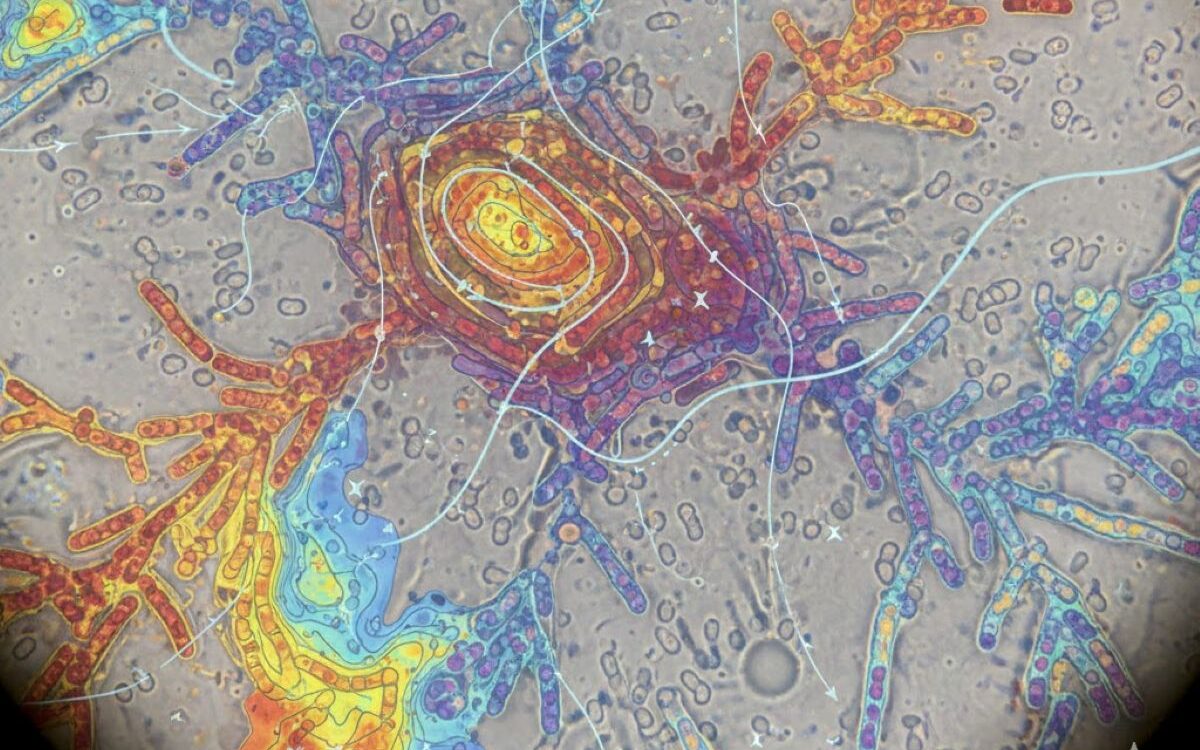

Two recent studies from Arizona State University describe novel forms of movement in bacteria that lack functional flagella. In one investigation, strains of Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli were found to migrate across moist surfaces even when their flagella were disabled. The researchers have termed this process “swashing”, a movement driven by chemical gradients produced during sugar fermentation.

In another study, scientists explored the behaviour of flavobacteria, which naturally lack flagella. They discovered that these microbes use a molecular conveyor belt system, powered by the type 9 secretion system, to glide smoothly across surfaces. A gear-like protein, known as GldJ, acts as a switch to alter direction, giving these organisms a surprising degree of control over their movement.

“Swashing”: Movement via Metabolism-Driven Fluid Currents

The swashing phenomenon occurs when bacteria ferment sugars such as glucose or maltose, producing acidic by-products like acetate and formate. On a moist surface, these compounds draw water outward, generating tiny fluid currents that carry cells forward.

When the Arizona State University team disabled the flagella of E. coli and Salmonella, they expected the bacteria to remain stationary. Instead, they found that colonies migrated freely across the surface. As one of the researchers explained, “We were amazed by the ability of these bacteria to migrate without functional flagella – the bacteria moved with abandon.”

The experiments showed that this movement only occurred when fermentable sugars and acid production were present. When the scientists added surfactants to disrupt surface tension, movement ceased. This indicates that swashing is distinct from classical flagella-driven swarming and relies on surface fluid dynamics rather than mechanical propulsion.

These findings have potential implications for healthcare and industry. On moist surfaces such as catheters, medical dressings or food processing equipment, bacteria might spread even when their normal motility apparatus is inactive. Modifying surface sugar levels, pH or material chemistry could help limit such colonisation.

Conveyor Belt Gliding: Molecular Motors Without Propellers

In the flavobacteria study, researchers uncovered how bacteria without flagella manage to glide across solid surfaces. The type 9 secretion system was found to power a molecular conveyor belt embedded in the cell membrane. This belt, coated with sticky proteins, moves continuously along the cell surface and grips the substrate to pull the bacterium forward.

The GldJ protein acts as a gear-like component, allowing the bacterium to change direction or reverse its movement. This system not only facilitates motility but also governs the secretion of enzymes and virulence factors, making it a critical mechanism for bacterial survival and colonisation.

The discovery suggests that inhibiting the type 9 secretion system could serve as a dual strategy: halting both bacterial movement and secretion of harmful substances. This insight could inspire new antimicrobial treatments.

Why This Matters: Biology and Beyond

These studies fundamentally challenge the long-standing belief that flagella are the universal mechanism for bacterial propulsion. They highlight the adaptive versatility of microbes, showing that even when stripped of their traditional motors, bacteria can still find ways to move and spread.

In a biomedical context, this has major implications. Therapies designed to inhibit flagellar motility might overlook alternative systems, allowing bacteria to persist and colonise surfaces. As researchers from the Arizona State University team remarked, “The more strategies bacteria have, the harder they are to contain.”

Beyond medicine, these findings may influence biotechnology and materials science. Understanding non-flagellar motion could inform the design of bio-inspired micro-robots or synthetic molecular machines that mimic bacterial movement.

Broader Context and Historical Footing

Although non-flagellar motility has been observed before, these recent studies provide unprecedented mechanistic detail. Previous research has described bacterial motion resembling crawling, sliding or gliding, but until now the underlying forces were poorly understood.

Scientists have proposed that bacteria use methods akin to “Spider-man-like” adhesion and retraction, “caterpillar-like” movement along their surface membrane, or even corkscrew-style drilling through viscous materials. These new findings refine and confirm such models, offering a clearer picture of microbial locomotion.

Challenges and Future Directions

Several key questions remain unanswered. How common are these non-flagellar motility mechanisms among bacterial species? What environmental cues trigger their activation? And how do these systems influence infection and biofilm formation in living hosts?

Future research will aim to map the detailed structure of the conveyor belt motor and study the flow patterns of swashing under realistic biological conditions. Scientists also hope to identify small molecules that can block these alternative systems, potentially paving the way for new antimicrobial technologies.

Concluding Perspectives

The story of bacterial movement is turning out to be far more complex and fascinating than once thought. These discoveries demonstrate that bacteria possess a diverse toolkit for movement, from metabolism-driven surface flows to intricate molecular conveyor belts.

Understanding these mechanisms deepens our insight into microbial adaptability and may eventually lead to innovations in medicine, biotechnology and nanotechnology. The age-old question of how bacteria move has taken a new and surprising turn – and science has only begun to explore its full implications.