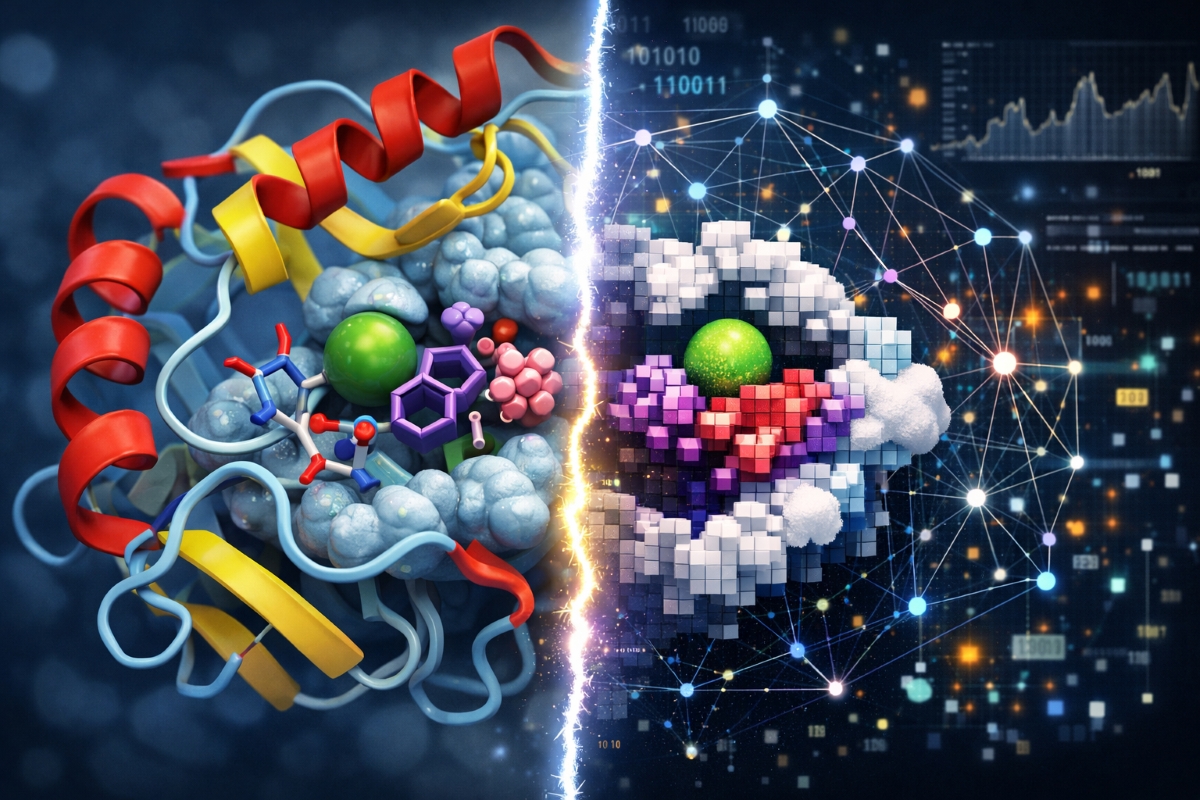

Generative AI has already changed what is possible in protein engineering. In the last few years, the field has moved from predicting protein structures to proposing entirely new proteins, often with experimentally verified folding and binding, at a pace that was unrealistic a decade ago. Much of that progress has been driven by the ecosystem around the Baker group at the Institute for Protein Design and the broader community building on similar ideas: diffusion-based backbone generation, inverse folding, and integrated structure–sequence pipelines that can be conditioned on a target. (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06415-8)

There’s a key technical distinction that matters enormously for biopharma: designing a binder is not the same problem as designing (or substantially improving) an enzyme. A binder can often be evaluated, at least to first order, by a static structural hypothesis: shape complementarity, buried surface area, hydrogen-bond satisfaction, electrostatic matching, and avoidance of clashes. Catalysis, by contrast, is a dynamical, multi-state, quantum-mechanical event embedded in a protein scaffold. The gap between “a plausible-looking active site” and “a reproducibly active enzyme with meaningful activity” is where AI/ML outputs fail.

The binder era: When AI-based output became experimentally testable

One of the earliest, clearest signals that deep models could do more than interpolate around known folds came from “network hallucination” approaches: take a structure-prediction network, invert it, and optimize sequences so the model predicts a confident, well-packed structure. In a landmark study, the team synthesized and expressed dozens of such hallucinated designs and showed that a subset folded cleanly; importantly, solved structures (X-ray and NMR) closely matched the designed models. (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-04184-w)

That result wasn’t “function” yet, but it was the enabling substrate. Once you can generate stable scaffolds, you can condition generation on binding interfaces and start solving problems that look more like drug discovery.

A canonical example is the de novo design of high-affinity SARS‑CoV‑2 spike binders: compact, stable miniproteins designed to engage the receptor-binding domain and block ACE2 interaction, with potent neutralization in cell-based assays. These are not antibodies, and they’re not derived from natural immune moieties; they are computationally designed proteins that behave like therapeutics. (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abd9909)

Diffusion models pushed this further. In the RFdiffusion framework, a RoseTTAFold-derived network is trained to denoise protein backbone “frames,” enabling unconditional generation and target-conditioned design for monomers, oligomers, binders, and functional motif scaffolding. The paper reports experimental characterization of hundreds of designs and includes structural validation, such as a cryo-EM complex of a designed binder with influenza hemagglutinin that closely matches the design model. (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06415-8)

More recently, the same toolkit has been extended into binding modalities long considered “undruggable” for small molecules and difficult even for biologics. For instance, de novo binders have been designed for peptide–major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) with specificity for the presented peptide sequence (a long-standing challenge because most binders default to MHC-heavy contacts). (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adv0185) And binders have been designed to recognize intrinsically disordered regions in extended conformations, a space where classical structure-based design struggles because the “target” is an ensemble rather than a single fold. (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adr8063)

What all of these successes share is that they are, at core, problems of molecular recognition. The energetic objective can be approximated by a (relatively) static bound-state hypothesis, and the experimental readouts, binding, neutralization, specificity, are often measurable in tractable high-throughput formats.

Enzymes are different: binding is necessary, catalysis is everything else

If binders are about stabilizing an interface, enzymes are about stabilizing a reaction pathway. That pathway includes:

- substrate binding (often with induced fit and solvent reorganization),

- formation of catalytic preorganization (productive geometry, protonation states),

- passage through one or more transition states,

- possible covalent or charged intermediates,

- product release and regeneration of the catalytic apparatus.

Even for “simple” enzymes, the chemical step is only one part of turnover; for many reactions, conformational gating and intermediate handling dominate observed kinetics.

A critical physical constraint is that enzymatic transition states are extraordinarily short-lived, on the order of femtoseconds, essentially the timescale of bond vibrations. That means we generally infer transition-state structure from isotope effects, transition-state analog binding, and high-level computation; we do not observe it directly in a crystallographic model. (https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-100742)

At the same time, proteins exist in different conformational landscapes time, and motions on fast timescales can enable access to slower, catalytically competent states. (https://www.nature.com/articles/nature06407) In other words: the catalytic event is a quantum-mechanical barrier crossing embedded in a fluctuating classical ensemble. A single “snapshot” active site geometry may look perfect and still be catalytically inert if it is rarely populated, incorrectly protonated, improperly solvated, or unable to support the full reaction coordinate.

This is why “hallucinating an enzyme,” producing a structure that resembles an enzyme active site, has historically been far less predictive than hallucinating a stable fold or even a binder.

Why “designing an active site” is harder than generating a binder interface

One temptation in the modern generative era is to treat enzymes as “binders to a transition state.” That appears to be reasonable, transition-state stabilization is central, but it is incomplete in ways that matter for designability.

1) Transition states are not structures you can train on

A crystallographic active site is typically a ground state: apo, substrate-bound, inhibitor-bound, or (at best) an intermediate mimic. The actual transition state is fleeting and inferred. Reviews of enzymatic transition states emphasize femtosecond lifetimes and the need for indirect measurement strategies (e.g., kinetic isotope effects) to constrain models. ( https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-100742)

A model trained on static structures is therefore learning correlations of catalysis, not catalysis itself. That can still be useful, but it limits how confidently we can extrapolate to “new-to-nature” chemistry where correlates may not hold.

2) Productive catalysis is an ensemble property

The presence of a catalytic triad in a single predicted conformation is not equivalent to a high population of catalytically competent microstates in solution. Protein motions span many timescales, and fast fluctuations can enable access to slower conformational changes that are required for catalysis. (https://www.nature.com/articles/nature06407)

For binders, a single well-formed bound state may be enough. For enzymes, the protein must repeatedly traverse an energy landscape that supports binding, chemistry, and release, with correct protonation and solvation at each step.

3) Electrostatics, pKa shifts, and water networks are “second order” but critical

Much of enzyme proficiency comes from electrostatic preorganization and fine-tuned transfer pathways. These depend on subtle features: second-shell residues, buried polar networks, dielectric properties, and structured water. The 2025 serine hydrolase design work explicitly highlights the importance of preorganization across reaction steps and shows that perturbing second-shell interactions can strongly affect activity. (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adu2454)

Generative models can propose plausible networks, but reliably scoring them, especially for a novel mechanism, still often requires physics-based or hybrid QM/MM evaluation, which is expensive and imperfect.

4) “Enhancing” an enzyme is usually easier than inventing one

If you start from an existing enzyme family, evolution has already supplied a working catalytic architecture and an ensemble that supports turnover. In that regime, ML can be extremely powerful: it can prioritize mutation sets, propose recombinations, and accelerate directed evolution cycles.

By contrast, de novo catalysis asks the model to build not just a stable scaffold but a whole mechanistic choreography. That is why early computational designs were often evolvable yet weak initially, improving substantially only after rounds of evolution.

So when will AI achieve truly new-to-nature catalysis?

If “new-to-nature” means reactions with no close natural analog, and catalysis competitive with evolved enzymes, then the bottleneck is the types of data available.

To cross the gap, models need training signals that reflect:

- multi-state compatibility (substrate, intermediates, product),

- quantitative kinetics (kcat, KM, kcat/KM) under standardized conditions,

- mechanistic annotations (rate-limiting step, isotope effects, pH-rate profiles),

- structural ensembles (not just a single snapshot),

- negative data (what doesn’t work) at scale.

Today, we have abundant structural data, but comparatively sparse, heterogeneous kinetic data; and we almost never have mechanistically resolved datasets large enough to supervise “design the reaction coordinate.” Even in cutting-edge diffusion-enabled enzyme design, the most successful workflows still embed human-chosen mechanistic hypotheses as constraints (e.g., specifying functional group geometries for catalytic motifs).

This is why the near-term future is likely hybrid:

- generative models propose scaffolds and motif placements,

- physics-based and learned surrogate models filter candidates across multiple reaction states,

- high-throughput expression and kinetic screening closes the loop,

- directed evolution remains the amplifier that converts “weak but right” into “strong and useful.”

The missing accelerator is a scalable enzymatic build-and-test as the dataset engine. This is where enzyme-enabled discovery and AI stop being competing narratives and can become unified.

As enzymatic methods expand what chemistries are accessible, especially under library-compatible, high-throughput conditions, they produce two valuable outputs at once:

- New molecules in real chemical space (often structurally complex, conformationally constrained, and “bio-interface-like” in how they engage targets).

- New functional data about how specific enzyme architectures enable specific transformations.

Those outputs are exactly what current AI struggles to invent from scratch when training data is absent. But once data exists, and is measured, screened, and annotated, it becomes learnable. This is the deeper synergy: enzymes make both products and useful datasets.

The Baker ecosystem’s trajectory illustrates the direction of travel. RFdiffusion began as a general generative framework validated across binders and assemblies, then moved toward increasingly atomic functional constraints; RFdiffusion3 is explicitly positioned as a broader “all-atom interaction” generator that can condition on non-protein partners. Meanwhile, enzyme-focused work is increasingly evaluated not just by motif placement but by compatibility with multiple catalytic states and by rapid experimental triage at manageable library sizes. (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41592-025-02975-x)

Conclusion – A pragmatic outlook for biopharma

A useful way to summarize the current frontier is:

- Binders are already in the “design → test → iterate” regime, where generative AI can routinely propose folds and interfaces that work, and experimental selection refines affinity/specificity.

- Enzymes are entering that regime, but with a heavier mechanistic tax: success requires designing not just a structure, but a trajectory, and our direct observations of that trajectory remain incomplete.

- The fastest path to “new-to-nature” catalysis is likely closed-loop design at scale, where enzyme-enabled synthesis and screening generate the mechanistic and kinetic datasets that generative models currently lack.

Enzyme design is powerful enough to warrant skepticism, orthogonal validation, and mechanistic honesty, especially as AI increases the rate at which plausible-looking candidates can be produced.

If the binder revolution showed that “hallucinated” proteins can become real, the next decade may show something even more consequential: AI-guided enzymes that don’t just recognize biology, but expand meaningful chemistry that biology, and biopharma, can explore.

Author Profile

Karsten Eastman, CEO

Dr. Eastman earned a PhD at the University of Utah under the mentorship of Professor Vahe Bandarian, where they discovered key processes that enable Sethera Therapeutics’ innovative technology. As a co-founder of Sethera, Dr. Eastman is leading the company’s efforts to commercialize cutting-edge peptide therapeutics, drawing on their experience in enzyme and peptide research, patent development, and engagement with key business mentors