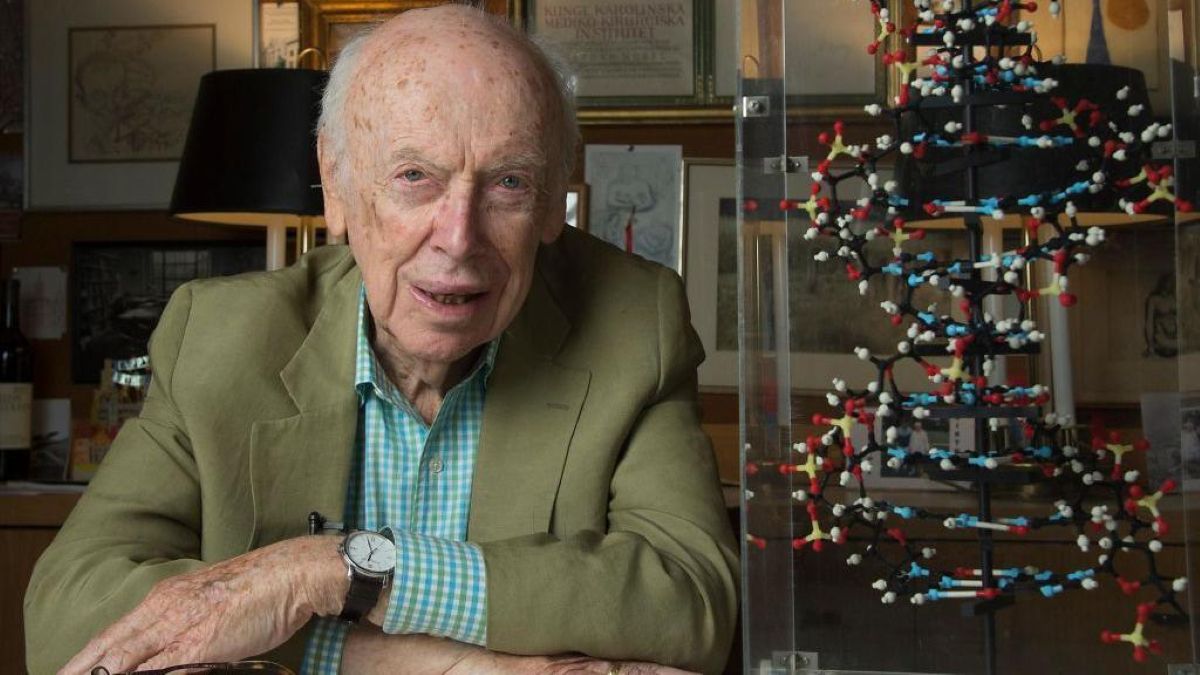

Renowned molecular biologist James D. Watson has died at the age of 97, his son and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) in New York confirmed. The scientist, best known for co-discovering the double helix structure of DNA in 1953, passed away following a brief illness in hospice care.

A discovery that changed biology

Watson, together with Francis H. C. Crick and Maurice Wilkins, shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on the molecular structure of nucleic acids. Their 1953 announcement of the DNA double helix marked a profound moment in science, showing how genetic information is stored and copied, and laying the foundation for modern genetics, biotechnology and genomics.

At the time, Watson was only in his mid-twenties, underscoring the speed with which the discovery took place. Colleagues later recalled the energy, confidence and, in some circles, irreverence of the young duo at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, where their model building and insight took shape.

A career of leadership and influence

Following the DNA breakthrough, Watson held prominent roles. He served on the faculty of Harvard University’s Department of Biology from 1956, and in 1968 became director of CSHL, raising its profile as a global centre for molecular biology and genetics.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Watson helped launch and advocate for the Human Genome Project, championing large-scale efforts to map the human genome. His drive was deeply personal; he often cited his son’s struggle with schizophrenia as a motivating factor.

He also contributed to major textbooks and wrote the memoir The Double Helix (1968), a candid account of the discovery process that remains widely read and discussed within scientific and literary circles.

A legacy complicated by controversy

While Watson’s scientific credentials are undisputed, his reputation in later years became increasingly marred by controversial remarks on race, intelligence and genetics. In 2007 he stated views suggesting a genetic basis for differences in intelligence among races, which drew global condemnation.

By 2019, after he reiterated similar statements in a documentary, CSHL revoked his honorary titles and publicly condemned his remarks as “reprehensible and unsupported by science.”

Francis Collins, then-director of the National Institutes of Health, commented:

“His outbursts, particularly when they reflected on race, were both profoundly misguided and deeply hurtful. I only wish that Jim’s views on society and humanity could have matched his brilliant scientific insights.”

At the same time, colleagues such as the biologist Nancy Hopkins, who worked with Watson in the 1960s, have acknowledged his early support for young women scientists, highlighting the paradox between his mentorship and his later public statements.

Impact and ripple effects

The discovery of the double helix did more than explain heredity. It enabled breakthroughs in genome sequencing, genetic engineering, forensic science, ancestry tracing and personalised medicine. Watson himself once said,

“There was no way we could have foreseen the explosive impact of the double helix on science and society.”

Yet the discovery also raised important ethical questions: about altering genes, patenting DNA sequences, and how societies handle the knowledge and power conferred by genetics. Watson opposed plans in the early 1990s to patent gene sequences, arguing that such information should remain publicly accessible.

Institutions such as the Francis Crick Institute and CSHL continue to advance the scientific fields that Watson helped establish, focusing on genetics, molecular biology and the ethical frameworks that accompany them.

For those seeking a deeper exploration of Watson’s life and controversies, the PBS American Masters: Decoding Watson documentary offers an unflinching look at the man behind the discovery.

Personal and final details

Born on 6 April 1928 in Chicago, Watson entered the University of Chicago at the age of 15 and maintained a keen curiosity for science from a young age, initially aspiring to study ornithology before shifting to genetics.

He died on 6 November 2025 in East Northport, New York. He is survived by his wife, Elizabeth Lewis, whom he married in 1968, and their two sons.

Remembering the man and the meaning

James Watson’s is a story of enormous scientific triumph and troubling ethical and personal contradictions. On one hand, he helped reveal one of the most elegant structures in biology, a spiral staircase of genetic information that underlies so much of life’s diversity and pathology. On the other, his later public statements served as a reminder that scientific brilliance does not exempt anyone from moral responsibility.

His legacy will endure in the laboratories, clinics and textbooks that rely on the insights his discovery furnished. Yet the debates he provoked about race, intelligence, genetics and how we wield knowledge remain very much alive.

As the scientific community acknowledges his passing, it does so with respect for his contribution and without ignoring the controversy. He exemplifies both the heights of human curiosity and the responsibility that comes with knowledge.