Decision Frameworks in Pharma: From RAVE and DICE to Lilly’s Truth-Seeking Machine

What Works, What Kills What, and Why It Matters

In pharmaceutical R&D, where billions ride on the flip of a biological coin, decision frameworks aren’t just nice-to-haves – they’re the rules that separate the winners from the not-so-greats.

We’ve all seen the headlines: Lilly’s GLP-1 juggernaut (Mounjaro and Zepbound bringing in over $20B in 2024 alone, and building the industry’s first $1 trillion company) versus the industry’s dismal 10-15% end-to-end success rate. But what’s the secret? Is it a scored ritual like Genentech’s RAVE, Pfizer’s pre-mortem autopsy in DICE, or something more… asymmetric? I wrote about those models in my last post, here…

This post distills a recent X thread sparked by that post. (A shoutout to @biobrainbox for the follow-up question on correlations to success rates.) I’ll compare the big three frameworks – Genentech/Roche’s RAVE, Pfizer’s DICE, and Eli Lilly’s integrated beast (Chorus + MILP optimization) – drawing lessons from my Substack posts on asymmetric bets and innovation traps. And, my 2023 IDEA Collider interview with Daniel Skovronsky, Lilly’s CSO, who discussed “truth-seeking” over wishful thinking. (If you haven’t watched it, you should: IDEA Collider | Dan Skovronsky. It’s 45 minutes that everyone should watch.)

MILP at Eli Lilly stands for Mixed-Integer Linear Programming.

MILP is a computational optimization technique that Lilly employs for portfolio-wide R&D planning and resource allocation. It models complex scheduling problems – such as balancing timelines, budgets, manufacturing capacities, and risk probabilities across their small-molecule and biologics pipelines – as mathematical equations to generate go/no-go recommendations and automated resource shifts. For instance, it can reallocate funding from underperforming oncology projects to high-NPV incretin assets based on updated success probabilities.

This approach was formalized in a 2020 collaboration with Carnegie Mellon University and is central to Lilly’s decision model, helping drive their ~25% end-to-end clinical success rate (vs. industry ~10-15%) by prioritizing maths over gut-feel (‘gut feel’ is often hidden by management consultancy-speak in many companies). It’s detailed in the paper “Portfolio-wide Optimization of Pharmaceutical R&D Activities” by Lilly researchers, available on Optimization Online.

The truth is that no framework is a silver bullet, but the ones that correlate with outsized wins (Lilly’s ~25% success rate, Pfizer’s pandemic pivots) share a core: early kills, maths over mood, and mechanisms to fight human bias. (I think it is worth crediting AstraZeneca for being an early leader with their 5Rs model (now 6Rs) as recorded in my interview with their previous Head of R&D, Mene Pangalos).

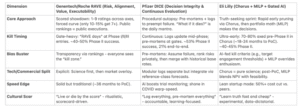

The Frameworks: A Side-by-Side Comparison

Pharma’s decision tools aren’t born in vacuums – they’re tested against Phase II attrition rates that compare badly to gambling. Here’s how the best stack up, based on public documents and posts, ex-employee writings, and my chats with insiders.

(Sources: NRDD 2012 on Chorus; Optimization Online 2020 on Lilly MILP; DIA talks on DICE; Genentech alumni blogs on RAVE.)

RAVE looks more like a gladiatorial arena – brutal and visible. DICE looks more like a lab review, dissecting risks before they escalate. Lilly? A venture studio, betting small to win big (echoing my Substack on winning small = winning big).

Spotlight: Pfizer’s Pre-Mortems – The DICE Dagger

If DICE has a killer app, it’s the pre-mortem. I have written for a long time about the pre-mortem, and its value, so it is nice to see it out in the world. (There’s also a video here…)

Mandatory at every gate (and ad-hoc for red flags), it’s used here for triage. Note: triage vs post-mortem – the right way to use Asymmetric Learning for good. Here’s the playbook, straight from Pfizer’s public statements:

- Fail Forward: Assume it’s 3 years out, and the project’s DOA. “What killed it?”

- Silent Storm: 10-15 mins of solo brainstorming – biology misses, safety scares, competitor ambushes. No chit-chat, no hierarchy.

- Rank & Reveal: Top 3-5 failure modes per person, then round-robin share. Repetition = signal.

- Reality Check: With base rates from Pfizer’s vault (e.g., “18% success for this mechanism”). Hard-headed calibration.

- Action or Die: Assign owners, experiments, deadlines. Log everything – audit trail for accountability.

- Rinse, Repeat: Logs live forever; unaddressed fears = career coffins.

It is possible that this saved Pfizer’s COVID bacon. Early 2020 pre-mortems flagged Covid variant escape, which gave rise to parallel manufacturing before Delta emerged. It’s why their success rates flipped from laggard (2% end-to-end in 2010) to leader, and one of the fastest and best decision makers in that period. Lesson? Pre-mortems harness imagination against optimism bias – the silent killer of 70% of late-stage flops.

Lilly’s Asymmetric Edge: Lessons from Dan Skovronsky

No framework chat is complete without Lilly (although my last post excluded them, while I looked for more evidence), the 2025 productivity and innovation beast (5+ approvals, 40% revenue from fresh launches – see my post Take one pharma company…). Their model’s no monolith: It’s Chorus (early “truth-seeking” unit, killing 70%+ on hard data) feeding MILP (the portfolio optimizer, detailed above, that reallocates ruthlessly) and AI gates (Magnol.AI predicting outcomes).

In my interview with Dan Skovronsky (timestamp ~15:00), he said: “We’re not in the business of hope; we’re in the business of evidence.” Chorus, born in 2003 to outpace Genentech, runs like a biotech accelerator: Nominate candidates, hit milestones (first-in-human, efficacy signals), exit fast if biology doesn’t come through. Result? Phase II success ~40%, costs halved. Dan credits it for tirzepatide’s dual-mechanism optionality – multiple paths to glory, minimal downside (straight out of my asymmetric bets playbook).

But here’s the Skovronsky phrase that struck me (~28:00): “Decision-making is where we lose the most. It’s not the science – it’s admitting when we’re wrong.” That echoes my Substack on sticking with failures: Phase I’s the real money pit, where wrong calls compound into billions lost. Lilly fixes it with “gardener” leadership (per Safi Bahcall’s framework in Pharma’s worst bet) – nurture diverse shoots, prune without ego. No senior leadership anointing losers.

Is there a correlation to their success? Lilly’s hotter streak (GLP-1 dominance) suggests yes – their model is modern: Speed + maths > ritual alone. But as Dan warned (~35:00), “Even we get it wrong. The key is learning faster than competitors.” (I’d like to highlight that – the industry’s most successful head of R&D points to the same key that this blog is based upon…)

Asymmetric Lessons for Your Portfolio

From my Substack, here’s the meta-framework – because no off-the-shelf tool survives contact with reality unchanged:

- Bet Asymmetric: Like Lilly’s tirzepatide (dual GLP-1/GIP), design for multiple wins, low maximum loss. (See Winning small = winning big.)

- Escape the Moses Trap: Ditch top-down decrees for diverse input. Bahcall’s “loon shots” need gardeners, not kings (Pharma’s worst bet).

- Pre-Mortem Religiously: Steal from DICE – it’s the ultimate bias mitigator. Pair with RAVE’s transparency for no-gos that stick.

- Truth Over Triumph: Follow Dan Skovronsky: Evidence gates early, maths late. AI’s a referee, not your cheerleader.

- Measure What Matters: Track Phase I kill rates, not just moves into Phase II. Fresh revenue % (Lilly’s 40% vs. J&J’s <5%) is your North Star (Take one pharma company…).

Pharma’s not broken – it’s biased. These frameworks prove discipline scales. But as I argued in Rethinking Pharma with Alex Telford, the real revolution is approving processes, not pills – unlocking scale for the next tirzepatide.